We believe time-bound targets will drive progress and ensure accountability on common goals . This has served England well – with the UNAIDS ‘90-90-90 target’ met early. To end new transmissions, we require measurable targets that provide concrete milestones towards our end goal . We believe both existing and new time-bound targets will drive progress and ensure accountability.

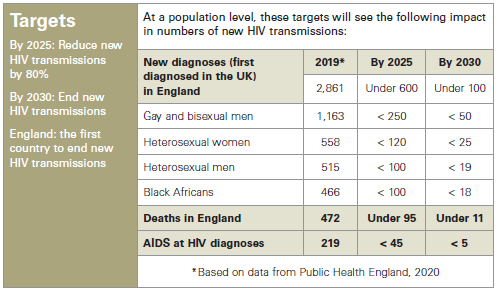

Decreasing HIV transmission targets should be applied to each key population in England – this is the only way progress will be equal across population groups . Success should be measured and reported by government to parliament alongside official HIV statistics every year . The ambitious target to reach an 80% reduction by 2025 is new and essential, as we know that the last transmissions will be the hardest to find and will require additional focus . To keep the country’s focus, the government must commit to England being the first nation in the world to end new HIV transmissions by 2030.

There has historically been no consensus definition of ending new HIV transmissions in England, as defining it is not easy . UNAIDS suggests an ‘elimination’ definition of less than one new infection per 10,000 per year . We heard during our evidence gathering process that the word ‘elimination’ can imply that we don’t want people living with HIV to lead healthy, long lives . Therefore, we have not used the word ‘elimination’ in this report.

England has already reached this level for the overall population . However, within key population groups and in some places around the country, the level of infection per 10,000 in the population is a lot higher . Therefore, our targets seek to define our goal in a meaningful and measurable way for relevant sub populations.

There are also still significant numbers of new HIV transmissions, many living with undiagnosed and untreated HIV and far too many deaths in 2020 in England related to untreated HIV – these are all areas where further progress is possible.

In the UK data is collected on how many people were newly diagnosed with HIV in each year . These newly diagnosed people may have acquired HIV recently, or some time ago . Those people who have been living with HIV for some time are described as a ‘late diagnosis’ – this is problematic because the person is likely to become ill and have much greater health concerns and a higher risk of death . They also remain infectious and able to pass HIV on . The UK also uses a range of methods to also estimate HIV incidence – the number of people who acquire HIV in each year.

In order to know we are making progress, we need to know that with the same or increased numbers of HIV tests, both the diagnoses and incidence rates decline . By reducing diagnoses whilst testing the same number we know that we are finding those living with HIV and able to pass it on . By reducing the incidence level we know that the actual number of people acquiring HIV each year is reducing.

The Commission has set targets, which we believe are essential for motivating and evaluating efforts to scale up and sustain prevention efforts until ‘transmission has ended’ . We believe that targets measuring the number of new diagnoses first diagnosed in the UK will be the most effective measure – these figures breakdown by both nation and by important sub-demographics . It is important that the reductions projected for gay and bisexual men are mirrored across all groups . Concurrently, it will also be important to see the incidence level continue to reduce – demonstrating that this approach is successful.

HIV is a global issue and one which does not respect geographic borders . In England, 53% of HIV diagnoses made in 2019 were among people born abroad . The most common regions of birth for migrants newly diagnosed with HIV in England in 2019 were Europe (ex-UK) (16%), Africa (10%), Eastern Africa (9%), Asia (8%). There is also a significant cohort of people born in the UK who acquired HIV whilst travelling or living abroad . In 2019, they represented 15% of new infections in people born in the UK, with this group more likely to have acquired HIV through heterosexual contact.

The term ‘health tourism’ has been used by some politicians and in the media to imply that some people come to the UK to benefit from free healthcare at cost to taxpayers . No evidence to support this claim was found or reported to the HIV Commission . Instead, we received reports that charging for other aspects of healthcare and the sharing of data between the NHS and immigration enforcement often deters migrants from seeking the care they are entitled to, even though HIV care is universally free . Meanwhile, in 2018, short-term visitors to the UK receiving ART (a form of treatment for people living with HIV) accounted for only around 1 .2% (about 100) of those accessing HIV services . We believe that universal access to testing, care and treatment is the cornerstone of HIV prevention in the UK . As Commissioners, we have identified many things that need to change to meet our ambitious targets, but none of this will work without maintaining universal access to HIV treatment and ensuring that this is widely promoted . This foundation is essential, but we have a long way to go to ensure that everyone is aware of this right to HIV care and is supported to access these services.