Ensure there are the right resources to meet the 2025 and 2030 goals

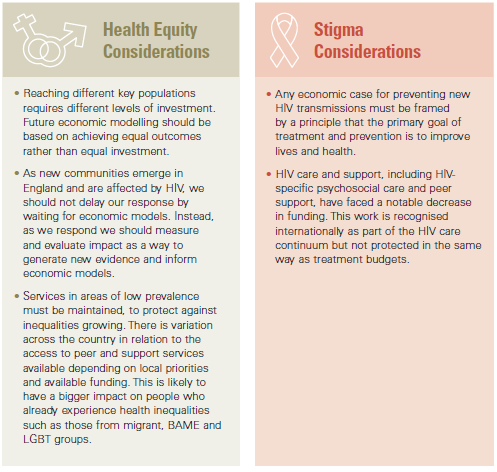

Funding for the HIV pathway comes from multiple sources . HIV treatment and clinical care is funded as part of the national NHS England budget, while many HIV (and other sexual health) prevention services are funded by local authority public health grants . While NHS England funded services continue to receive (much needed) increases in funding, the local authority public health grant has seen consistent cuts (14% in real terms between 2014-2018) and sexual health budgets have borne more of these cuts (being cut by 25% 2014-2018) . HIV testing is currently commissioned via several pathways and testing strategies are in part determined by HIV prevalence . In order to improve diagnosis, new testing strategies will be required, and current cost-effectiveness models challenged.

We know that any response must be properly resourced to be successful . By resources, we mean financial investment but also people, knowledge and tools . This includes a well-trained and supported workforce and access to information, prevention and care for everyone . Unlike the NHS budget, public health (including sexual health) spending has not been protected and has been cut by £700 million in real terms since 2015 . Cuts are already having an impact on sexual health services . In some parts of the country in services provision, lower staffing levels, and reduction of sexual health advice and prevention activities threaten the progress achieved to date . Many services are unable to meet demand, with London’s largest sexual health clinic, 56 Dean Street, reporting in 2018 that they had roughly 1,500 patients a day trying to book onto 300 available appointments .55 Support services have also felt this impact .56

In 2016, the cost of HIV treatment per annum when HIV is diagnosed quickly was estimated to be around £14,000 per case compared with £28,000 per case when diagnosed late . Each infection per person is estimated to represent between £280,000 and £360,000 in lifetime costs to the health system .57 These future treatment costs can be avoided by investing in HIV prevention and ending new HIV transmissions . Additional investment in HIV prevention will provide a long-term financial benefit to the healthcare system by reducing healthcare costs as a result of avoided new infections and delayed disease progression .58

“The underfunding of community and public services at large make it even more difficult for many people on the margins to be resilient and

exercise control over the direction of their own lives.”

Dr Catherine Dodds

HIV care and prevention in England was already failing to meet demand before the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Now, as well as a continued shortage in resources for publicly funded interventions, many already stretched voluntary organisations are struggling to survive . The voluntary sector provides advocacy, support services, peer support, and testing . These services have often borne the brunt of cuts to funding and have been amongst the quickest to adapt in the face of the pandemic. A loss of resources has come at a time when more people than ever are living with HIV . Even if we achieve progress towards our goal of reducing and ending new transmissions, the number of people living with HIV will continue to rise . Our plan to end new HIV transmissions requires investment in prevention, so that services don’t just struggle to deliver the minimum required but can innovate and accelerate our progress.

In Birmingham, stakeholders reported that the Heartlands HIV Clinic does an incredible job to support people living with HIV . Patients were proud of the clinic and had established a patients’ forum for peer mentoring . However, the service is stretched and is meeting needs that should be supported by other services . In contrast to Bristol, Manchester and Brighton, there are no funded charities in sexual health in the area, which all commented on as being a big loss to the city . This is despite that fact that residents in the Midlands and East of England region contributed to the highest number of new diagnoses outside of London (23% (660 / 2,861) in 2019 . Fifty percent of those living with HIV in the area were diagnosed late, above the national average . A number of responses received by the Commission noted the problems caused by the separation of HIV services commissioned by NHS England and sexual health services, commissioned now by local authorities, has been made worse by the absence of voluntary sector provision in many areas of the country .

“There also should be more acknowledgement of the prevention work that is integral within the support of HIV positive clients by the third sector, maintaining their wellbeing, giving increased assurance to treatment adherence and less risk-taking, hence, reducing HIV transmissions.”

Blue Sky Trust

If people living with HIV are given the support they need, advances in treatment mean that we will continue to see people living with HIV for many decades to come and therefore HIV clinical services that meet their needs (especially an ageing population) must be sustained . Alongside this, while the number of HIV diagnoses decrease, and it becomes more expensive to find and diagnose a case of HIV, it is likely to get more and more difficult to protect HIV specific funding, despite the fact that the needs of people living with HIV remain the same . As new technologies come to market – new ways of taking PrEP, more accessible or acceptable HIV treatments – a clear case will need to be made for why a new technology should be funded by the NHS for a health condition that is in the future, we hope, declining in prevalence.

Newly developing Integrated Care Systems allow the opportunity to develop and sustain the collaborative care models required to manage HIV as a long-term condition . NHS England is developing a Category Based Management approach to procuring and commissioning ART . This will be more closely aligned to the BHIVA Treatment guidelines and allow an evidence-based but more holistic approach to drug treatment.

Each year, local and national bodies commit significant financial resources to the fight against HIV . They help increase the reach and effectiveness of HIV services, research, health promotion and treatment. However, over £700 million in cuts to the public health budget since 2014/15 have led to sexual health service budgets being cut by 25%, impacting the provision of prevention services and risking our HIV progress to date. This is in the context of increasing demand for sexual health services and a growing population living with HIV.

The HIV workforce

We were deeply moved by the dedication of the HIV workforce, with many going well above their duties to care for people living with HIV and prevent new transmissions . We spoke to nurses, doctors, staff at community organisations and public health teams, who were all deeply committed to their roles and feeling stretched and burned out . Many told us that they spent additional time filling gaps and providing parts of care that they shouldn’t have to have been doing. Many felt this work went underappreciated.

The sexual health, reproductive health and HIV workforce in England has never been as fully defined as other clinical specialisms . This workforce covers a broad range of clinical and non- clinical, specialist and non-specialist staff providing services from hospitals, primary care and community settings . Over the past few decades, shifts in healthcare in general as well as in the nature of HIV care have put substantial stress on the HIV workforce . There are two interrelated challenges for the workforce over the next decade: maintaining the specialised HIV workforce, while educating the general workforce better about HIV.

There are problems of retention and recruitment of the workforce across the whole HIV care pathway, which pose a problem if the UK is to maintain its status as world leader in HIV care .59 For example, only 37% of genitourinary medicine (GUM) and HIV/AIDS physicians work full time. The commissioners of sexual health, reproductive health and HIV services rely on staff being available and suitably qualified to match to the requirements of the service . They do not, however, always commission services taking full account of ongoing training needs and how the workforce will develop in the future to meet emerging needs . A significant decline in AIDS-related morbidity and mortality has been the big success of the world-class treatment provided for HIV in England . This means that the HIV workforce is now managing an ageing population of people living with HIV, with an increased risk of age-related comorbidities . Even as new HIV diagnoses decline, it will be decades before we see a significant decline in the total population of people living with HIV. This is welcome. We want people living with HIV in England to live long and healthy lives, and we need to maintain a workforce to facilitate that . Normal life expectancy for many with HIV, and an ongoing decline in new HIV diagnoses, will mean a population of people with HIV with an average age older than the general population . Combined with the higher rate of age-related conditions, our services must evolve to manage multi-morbidities, polypharmacy, psychosocial issues, residential/nursing care services and end-of-life care, to maintain excellent HIV care outcomes.

Success in ending new HIV transmissions by 2030 will not mean that our work is complete . Efforts to maintain our progress and ensure people living with HIV can lead healthy and fulfilled lives must continue and a trained workforce will be essential to this . Further to this, a trained HIV workforce will have a broad range of transferable skills which will make them well placed to be deployed in other public health efforts and beyond . Investment in people and skills for HIV are therefore as much a long-term investment as a shorter one to meet our 2030 goal . This has been the case with COVID-19, with many lessons already learned in HIV applicable to this new pandemic.

“Our resources to deliver such innovative and evidence-based programmes are dwindling.”

London Borough of Lambeth, Public Health Department

At the moment, within clinical settings, we risk the number of specialised clinicians falling below the number needed for prevention and care . Within the voluntary sector, we risk losing services crucial to challenging structural inequalities, like BAME and Trans-led services and those enabling excellent care outcomes for a growing number of people living with HIV.

Access to HIV prevention and treatment tools

The success of combination HIV prevention is the principal explanation for the fall in HIV incidence among gay and bisexual men in England . We need to translate this progress across all populations and regions of the country . We will only achieve our goal through sustained, ongoing health promotion, which utilises all the tools of combination HIV prevention. We know from the experience of the PrEP IMPACT Trial that if prevention tools are not accompanied by health promotion activities, inequalities in access are exacerbated . Only if we commit to sustained and comprehensive promotion of combination HIV prevention will our message reach everyone.

We have the tools available to end new HIV transmissions . Recent falls in HIV transmissions have been attributed to combination HIV prevention: an increase in HIV testing uptake, more people on HIV treatment making their viral load undetectable, continued use of condoms and the uptake of PrEP .60 PrEP is the newest combination prevention tool . It is a drug taken by HIV-negative people before and after sex . Evidence shows that PrEP is almost 100% effective when taken as prescribed .61 Since the evidence of PrEP being effective became known, activists and clinicians worked to ensure PrEP was available via the health system as a prevention tool. Initially, NHS England argued that it would not fund PrEP, arguing that prevention was not part of its commissioning responsibility . After the National AIDS Trust’s successful legal challenge in 2016 and the Court ruling on NHS England’s ability to commission of PrEP, the IMPACT trial opened in 2017 with 10,000 places . Eventually this made PrEP available to 26,000 people . The cap on places had life-changing consequence for 15 people on PrEP waiting lists; each was confirmed to be HIV negative at their first assessment for the trial and are now confirmed to be HIV positive.62

In March 2020, the government committed to make PrEP fully available, uncapped, on the NHS. This was a huge victory for those who have been tirelessly campaigning for PrEP to be made available through the NHS for the last five years, since the Proud Trial proved that PrEP was effective in preventing HIV transmission. Since, we have been disappointed by further delays and £5 million being cut from the £16 million budget intended to make this available . We believe it is essential that PrEP is made available, fully funded and on an ongoing basis, if we want to achieve our target.

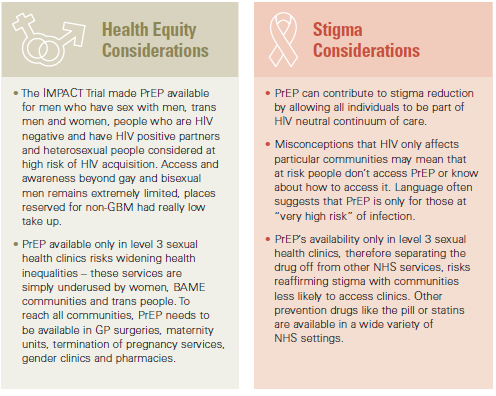

Despite this announcement, at the time of writing, bureaucratic delays mean that in most areas of England, the PrEP service is still not available. Commissioning of PrEP will facilitate access to the sexual health pathway of care which offers an opportunity to consider sexual health and wellbeing more holistically and ensure STIs and reproductive health are also addressed . However, sexual health services should not be the only way to access PrEP on the NHS – the exclusivity risks widening health inequalities with women, BAME and trans people much less likely to access these services, let alone rural communities physically far away from this provision . The need for additional pathways to ensure equity of access including access via primary care (including non-traditional delivery for example, app-based provision of GP services), maternity, and termination of pregnancy services but also gender clinics and even pharmacies . If the high street retailer Superdrug can provide PrEP through its ‘online doctor’ – a welcome development – it must be possible for the NHS to provide PrEP in healthcare settings more regularly frequented by all communities . As the national PrEP guidance from BASHH and BHIVA states, “limiting provision of PrEP to level 3 sexual health clinics risks widening health inequalities disproportionately among black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) populations .”

Public Health England attributes recent declines in HIV diagnosis to combination prevention, the role of much wider and more frequent testing as well as rapid access to effective treatment for those who are diagnosed . In 2016, a significant decrease in HIV diagnoses in sexual health clinics in London has been attributed partly to gay and bisexual men at high risk of HIV infection buying PrEP themselves, before the IMPACT Trial .63 England’s largest sexual health clinic, 56 Dean Street, in Soho, saw a 40% decline in new diagnoses in 2016 . The clinic attributes the decline in part to PrEP but ‘not just PrEP’, with other factors such as rapid initiation of treatment, prescribing of PEP (post-exposure prophylaxis, a treatment that can stop an HIV infection after the virus has entered a person’s body) and the Dean Street Express testing service . We also know that globally, cities where PrEP is available are seeing more rapid falls in HIV incidence than cities that are not providing PrEP . As part of combination prevention, PrEP offers the opportunity to accelerate population declines in HIV incidence .

It is clear from the evidence we collected, that while it is common sense to invest in prevention, to prevent larger care costs down the line while improving lives, there is a lack of clear, specific data that justifies this . This hinders funding bids at every level, as organisations are unable to provide figures to support appeals for resources . As an HIV commission, we have come across this same difficulty . A combination of methods is needed to address the dynamic needs of individuals . Understanding the return of investment of combination HIV prevention is fundamental to assess value for money, a key piece of information in the development of local and national budgets . Trying to understand what the full scope of this investment is, remains a key challenge that needs to be addressed.

“We do not have adequate return on investment data for HIV interventions, and we do not know what constitutes an acceptable level of return on investment from preventing onward HIV transmission for different prevention efforts. This greatly stifles the ability to have clear

economic deliberations when it comes to why investment in HIV prevention is so vital.”

Terrence Higgins Trust

While the cost of treating HIV remains high, financial efficiency could be improved by optimising the use of generic (non-branded) medication for treatment and prevention to mitigate the lifelong costs of HIV treatment and PrEP . Earlier implementation of generics as they become available offers the potential to maximise the scale of financial savings .64 New biomedical prevention technologies, including vaccines, different formulations and methods of delivery of PrEP and antiretroviral medications (such as via long-acting injection or implant) are in development and likely to be licensed before 2030 and important further tools in our shared aim to end new transmissions.

Starting this academic year, sex and relationships education (SRE) will become a mandatory requirement for all secondary schools in England . Guidance includes that pupils should know about STIs, including HIV, safer sex, and the importance of and facts about testing . This includes that ‘effective teaching should aim to reduced stigma attached to health issues, in particular those to do with mental well-being’. We welcome this change towards mandatory SRE in all schools.

The Sex Education Forum told us that in 2018, over a third of young people they surveyed had either learnt nothing about HIV in school or not learnt what they need to .65 The move towards mandatory SRE was mentioned by stakeholders at multiple evidence hearings across the country . Particularly, many people proposed that teachers must be funded and supported to have proper training and up-to-date information about HIV to ensure that teaching tackles, rather than perpetuates, stigma . At our meeting in Manchester, it was suggested that community organisations might be well placed to deliver training in schools .66